This feature by Christopher Frayling was first published in Document 16: Design City, distributed with Creative Review in February/March 2017.

Ken Adam, the production designer of ‘Dr Strangelove’, was born in Berlin in 1921 and died in London in March 2016 aged 95.

After RAF service in the war, Adam became an Art Director with ‘Around The World In 80 Days’, a mid 1950s film for which he won his first Oscar nomination. His big breakthrough movie was ‘The Trials of Oscar Wilde’ (1960), for which he won his first award at the Moscow Film Festival, chaired by Luchino Visconti. It was his design of the James Bond film ‘Dr No’ in 1962 that got him the job with Stanley Kubrick designing ‘Dr Strangelove’.

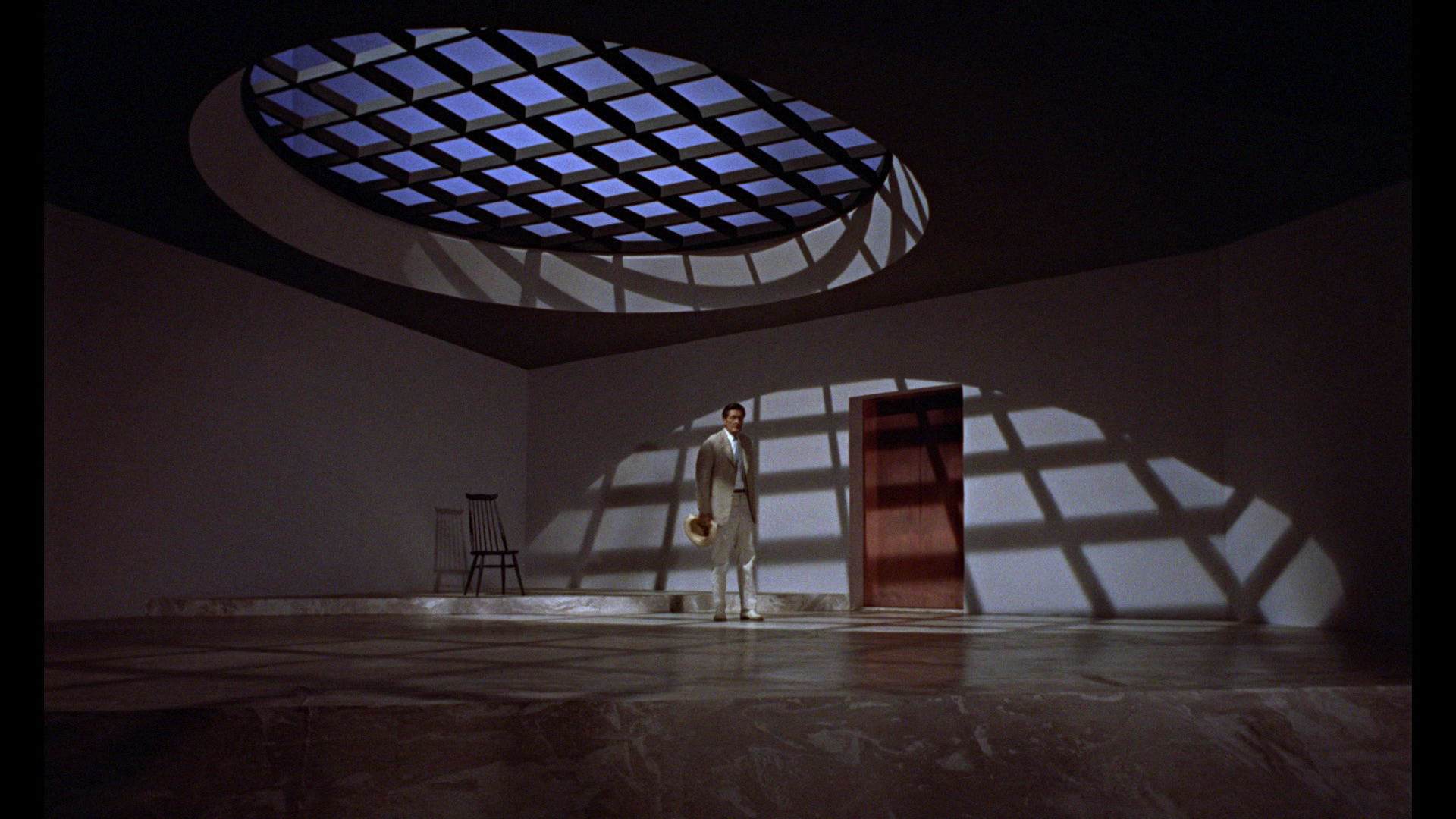

Growing up in Berlin in the 1920s, Ken’s formative influences were the Bauhaus for architecture, and expressionist films like ‘Dr Caligari’ and ‘Metropolis’, which made an indelible impression on him – there is undoubtedly an expressionist theme in Ken’s designs. When we are first introduced to ‘Dr No’, we see Professor Dent standing in this extraordinary room with a circular grill which looks like a spider’s web and throws shadows on the wall and floor, and you just hear the voice of Dr No saying, “Professor, you have failed me” and then a tarantula appears. It clearly bears the stamp of Ken’s formation in Berlin, like a still from ‘Dr Caligari’. The budget for ‘Dr No’ in total was only £350,000. The amount for sets was £20,000 and this set cost £320. It wasn’t done on a large budget. The later Bonds of course became a spectacular success, but at this stage, this was a small scale British film he was working on.

The film opened in London late 1962, and Stanley Kubrick went to see it the very first day. Kubrick realy liked two sets in the film – the nuclear reactor and Professor Dent with his circular grill. He got in touch with Ken and they talked about ‘Dr Strangelove’, which was based on a nuclear thriller about a B52 bomber that flies towards Russia and they can’t get in touch to call it back. Kubrick decided the only way he could make nuclear Armageddon palatable was to turn it into a black comedy.

Ken did some sketches for the three main sets: the War Room underneath The Pentagon, the B52 bomber flying towards the Soviet Union, and the office of General Jack D. Ripper, played by Stirling Haydon at Burpelson Air Force base.

Stanley Kubrick was like a boy scout. He loved switches and playing with elaborate bits of technology. He wanted to shoot the film in three distinctive styles: a documentary style inside the plane, a handheld Arriflex camera for Burpelson Air Force base as if it was a newsreel, and expressionism for the War Room. Three clashing styles, three different kinds of comedy.

In those days there were a lot of war surplus aeroplane parts in junk yards and scrap heaps all over London, so Ken’s assistant went round and assembled an authentic-looking dashboard for a B52: lots of switches, lots of lights, lots of things that looked authentic, though actually it was complete fiction. He also got hold of the latest issue of ‘Jane’s Fighting Aircraft’, which had lots of exteriors of the American B52 bomber.

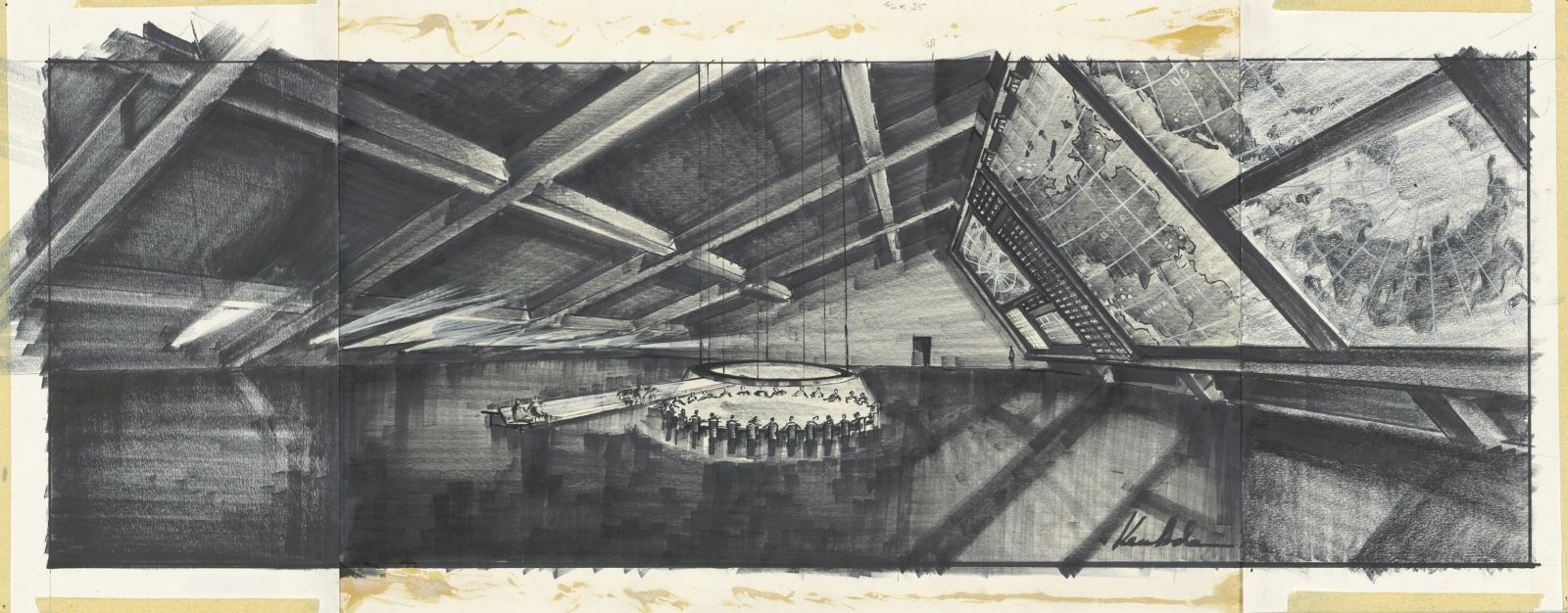

For the War Room, all Ken had to go on was the shooting script which says: “Interior war room, see black and white photo” referring to a picture of the headquarters of the North American Air Defence System in Colorado: a series of small tables with screens, some desks, filing cabinets and consoles – like an office, but with a few screens. Ken tore it up and said “That’s much too boring, not very exciting for the War Room”.

What he came up with was what Steven Spielberg has called the greatest set in the whole history of the movies. It’s underground, underneath the Pentagon. They wanted it to be huge and very claustrophobic and the way to do that was to have a ring of light over the table as the main light source so you don’t quite know where you are.

Ken did his first design very quickly, and Kubrick okayed it, but the problem was that he’d put a second level in it, where people would stand and look down on the discussions of the War Room – a bit like Norman Foster’s Reichstag, where you can see all the debates. They had already started building it, the technical drawings were done and the models were done when Kubrick said “What am I going to do with all those extras standing there just wandering around like lemons? They’re expensive, they don’t play any part in the story, you’ve got to get rid of that.” Ken was quite upset that the thing they’d agreed was vetoed very early on, but as Kubrick said, “I reserve the right to change my mind, not only until filming but during filming as well”, and he changed his mind a lot.

So Ken started doing a much looser drawing, much more expressionist, with sloping walls and ideas of light. This is where he begins to get into focus. It’s going to be triangular. It’s a concrete bunker underground. It’s a circular table with green baize on it, not polished wood, so it feels like a poker table. Even though it’s in black and white, he wanted the people sitting round it to feel like they’re playing poker for the future of the world. Vatican chairs, so you get a feeling of cardinals sitting around a table. Where possible, the only light source is a light ring suspended above the table and the rest is black. So you have a mixture of a gambling table, a committee thing and the policy making of the President of the United States and his Chiefs of Staff.

A wonderful touch, which Ken came up with, was a polished black floor that reflects what’s going on above it – he had in mind Fred Astaire musicals of the 1930s. They took up the floor of the entire studio, applied a soft undercoat, like an underlay of a carpet, very thick wood to make it absolutely even and then they sprayed it. No one was allowed to wear shoes while filming – they had to wear fabric slippers, otherwise it scuffed the floor. So you have the dark floor, the table, the light ring and the triangular construction of reinforced concrete. You’re living in a bomb shelter as well as underneath the Pentagon – in short, you’ve got the War Room.

The classic thing with sets like this is that you do the establishing shot to show where you are, then the medium shot and then the close up. But they decided to abandon all the long shots because it wasn’t claustrophobic enough. Instead you arrive in the middle of a discussion, sometimes you see it from above, sometimes from the side, but you’re never quite sure which part of the room you’re in, how big the room is, where the ceiling begins and so on. It’s a vast set that feels claustrophobic – really clever and absolutely deliberate.

Then on the sloping walls you have huge maps which look terribly high tech, but they were actually just drawings which were then blown up on photographic paper and stuck onto plywood, then holes were punctured into the plywood with perspex over them, and behind each of these holes is a 100-Watt lightbulb with a switch for each bulb. As you track the nuclear bombers on their way to the Soviet Union, it looks fantastically high tech, but the whole thing was really low tech.

At the end of the film, Dr Strangelove appears in his wheelchair – ex-Nazi rocket scientist, played by Peter Sellers, who also plays the Wing Commander and the President of the United States. Dr Strangelove keeps going into Nazi mode, he refers to the President as Mein Führer by mistake and his arm goes into an involuntary Nazi salute. At the end of the film he stands up and says “Mein Führer, I can walk!”. Cut to newsreels of nuclear explosions, with Vera Lynn singing ‘We’ll Meet Again’ from the Second World War – Ken’s idea, actually.

In between, there was a famous six-minute sequence that was cut and does not appear in the film, of a huge custard pie fight in the War Room – it’s in the National Film Archive. The Russian Ambassador is caught spying in the war room, someone throws a custard pie at him, he throws one at George C. Scott. It’s complete mayhem, speeded up like Laurel and Hardy, with George C. Scott swinging on the light ring. The gag is that the President stands in the middle and doesn’t get touched, then suddenly a custard pie hits him in the face and George C. Scott says, “You have struck down the President in his prime”.

John F. Kennedy was shot during post-production, so this is one reason Kubrick didn’t want to feature that line but also, if you see the sequence, it really doesn’t work. It goes over the edge of black comedy into slapstick, but there is a surviving still taken by Weegee, the photographer, of the custard pie fight in the War Room.

Finally, when Ronald Reagan became President of the United States and he made his first visit to the Pentagon, he said to his Chief of Staff “Can I please see the War Room?” And the Chief of Staff had to tell him, “Mr President, there isn’t one”.